We were intrigued by the myth of an Egyptian lord who, having lost his wealth and mind, now roams the streets of Maadi selling towels and narrating tales of his glories past. So we head to the street where Valentina Primo instead discovers a very different story but one of dignity nonetheless…

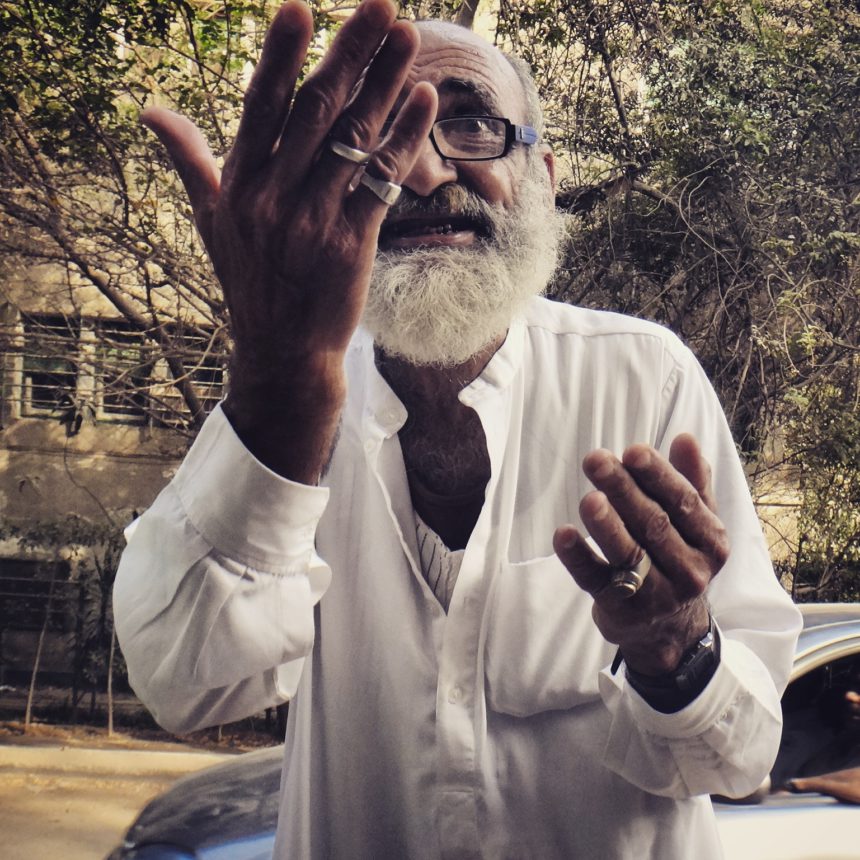

He has no idea who we are, but Mohamed Hassan greets us as if he has been waiting for months. He rises from the dust-covered mat where he sits every morning, selling towels and dusters to passers-by. We were lured in by an urban legend that says he was once a rich aristocrat who lost his wealth and mind to nationalisation, but as we meet him, we realise his story is a multi-threaded canvas of resistance and dignity.

He opens his mouth and his every muscle speaks. “I faced a lot of difficulties in my life,” he says. His tales, often dramatic, acquire a peculiar grace when framed by the candidness of his eyes. Originally from Khartoum, Sudan, Mohamed moved to Egypt when he was six-years old and developed his métier working in a construction company, until an incident turned his fate around. He pulls up the sleeve of his galabeya as he shows us the scar of the wound that would sign his sentence to unemployment. “I had actually signed my fate it since the beginning,” he says. “When the company hires you, they have you sign two different contracts: the first one for accepting the job; and a second one, resigning, so that if anything happens they can let you go easily.”

Mohamed peers above his electric blue glasses to make his point clear. His white long beard frames a complexion carved by years of struggle, in stark contrast with the pristine galabeya that perches on his slender body. Each scar on his left arm is a testimony of his suffering, but Mohamed does not dramatise. “I woke up at the hospital after the anesthesia had run out, very fatigued. They were able to save me and stitched my arm, but when I asked the doctors for pain killers, they couldn’t give me any. Then I was transferred to a general hospital in Gomhoreya Street, but when the company doctor visited me, I asked him to get my treatment at home. I bought my own cotton swabs, my syringes and needles, and paid everything from my own pocket. Why wouldn’t I treat myself?” he tells us.

After three months hospitalised, Mohamed was left unemployed, injured, and penniless, so he decided to file a law suit. But at court, he was met with corruption, and unscrupulous gains. “It took me about a year; I was transferred to a court in Bab El-Khalq for another year, and then to the high court in Abbaseya to a forensics specialist… mawaweel! I had to sell all my possessions at home, a TV that I had bought, and the washing machine to be able to pay the lawyers,” he says.

Having lost everything he owned, Mohamed strove to find a job in a cleaning company, but as he saw his colleague left to die anonymously in the street, he refused to sell his dignity for a meager salary and resigned. “We were all together standing on the back of a truck moving very fast when a tree branch hit one of us and he fell off. Do you know what the company did? They took off his uniform and tossed him aside on the road so that it would look like someone who was run over by a random car. After I saw what happened to him, I decided I’m worth more than that,” he utters.

12 years later, and Mohamed is a legend in Maadi’s street 15, where he sells cleaning products. “What am I supposed to do? Start begging? I wouldn’t do that even if my life depended on it,” he says euphorically. Suddenly, he stops talking. He looks around, runs towards a 4×4 car parked across the street, and arms wide open, mimics the stealing of a wheel. He comes back, graciously running, as he says: “Some people do that. It would be easy to take a wheel and sell it for 10 pounds, but that’s not in me.”

His theatrical skills and mischievous eyes have gained the hearts of his neighbours, who dedicate special Ma’edat Rahman every Ramadan for him. This year, one of his frequent customers volunteered to announce to her neighbours online that he will be placed in Moustafa Kamel Square to avoid conflicts with other street vendors. “There’s a very nice doctor that comes by from time to time bringing Ramadan goods; last year, they climbed all over her car to the point of breaking her windows asking her ‘we7na! we7na! (What about us?)’. I wouldn’t want that to happen anymore. Everyone wants to take something from you.”

But beyond the holy month of Ramadan, Mohamed’s everyday life is a constant struggle shaped by economic crisis, stigma, and the fruits of the revolution. “I used to be able to make 150LE a day, but since 2011, I only make about 50LE,” he complains. When sales are good, he works until nightfall and takes the metro back home to Helwan, where his wife and his six children live. “We usually move from one apartment to another, because at the end of the year the landlord often does not renew our contract or adds extra fees, and if I cannot pay them he’d tell me he needs the apartment because his son is getting married. My furniture got destroyed with all this moving, but what can I do?”

Mohamed’s youngest child is in the 6th grade, but it is his eldest son who still puzzles him every day. “He doesn’t reply to you when you try talking to him, and I have tried so hard: I got him a teacher to tutor him, I tried to have him learn craftsmanship, but nothing worked,” he says. “One day, I grabbed a stick and tried to hit him to see if he would at least protect himself, but he did nothing.” It was at that moment that Mohamed realized his son had a mental disability and understood there was no hope in him helping with the house duties. “He’s 35 years old but he’s like a baby, when he sees the children playing in the streets he tries to join them as if he was one of them,” he says, still smiling. His brother works as a teacher in Saudi Arabia, but Mohamed does not want to ask him for help. “He already carries a heavy load on his shoulders.”

“I just hope God gives me more time. When I was younger I would have never agreed to sit here and work this way, but I am 66 years old now, what else is there to do? Sometimes, I sleep here next to a security guard on duty, I order to save the 2LE metro ticket to get home. I leave my kids just about enough money for a couple of days, I then go home to leave them more money and come back here in the hopes that tomorrow, god willing, I can sell more products and buy more things to sell.”

“You know…” he says, anticipating his tale with excitement, “I was once taking the metro, I hadn’t sold anything and was on my way home to see the kids. There was a man and a woman sitting in front of me, but I wasn’t paying attention to them, I was thinking about God. When I looked up, they gave me 50LE! I hadn’t asked for anything, it was fate who decided I would get that amount of money that day, if not at work, then in the metro!”

Mohamed’s favorite story is his trip to Germany, where he went after his father passed away. He aimed to search for a job, but two nights in a hotel evaporated the savings he had taken for a three-month stay. “It was 1974 and I was young, I hadn´t got married yet. I went from the airport to the taxi, arrived to the hotel, and two days later, 1,700 Marks were gone!” he says. Seeking to arrive to Frankfurt, Mohamed headed off to the train station, but took the wrong train. “’Oh! You took the wrong one,’ a stranger told me. He took me to his home, gave me an inflatable mattress to sleep on, and began playing some music and asking me to sing along.” Back at the railway station, some workers gave him coffee and cheese to eat. After that they took me to a housing place for youth, where he stayed for the following three months. “People were crying when I left,” he says. “I have beautiful memories there.”

Mohamed’s favorite story is his trip to Germany, where he went after his father passed away. He aimed to search for a job, but two nights in a hotel evaporated the savings he had taken for a three-month stay. “It was 1974 and I was young, I hadn´t got married yet. I went from the airport to the taxi, arrived to the hotel, and two days later, 1,700 Marks were gone!” he says. Seeking to arrive to Frankfurt, Mohamed headed off to the train station, but took the wrong train. “’Oh! You took the wrong one,’ a stranger told me. He took me to his home, gave me an inflatable mattress to sleep on, and began playing some music and asking me to sing along.” Back at the railway station, some workers gave him coffee and cheese to eat. After that they took me to a housing place for youth, where he stayed for the following three months. “People were crying when I left,” he says. “I have beautiful memories there.”

As we conclude the interview, Mohamed stretches his hand into a bag and pulls out some incense as a present for us. The ragged mat awaits for him as the sun begins to drop down. Mohamed is not the Egyptian lord we headed off to find. He was not a rich man who bears witness to Egypt´s history of deprivation, but a symbol of resilience and dignity in a society that praises humble morals but stigmatizes humility. “The best thing I’ve learned in life is to never let my children work in the private sector,” he says. “Do anything! Sell towels, perfume, tissues, sell anything you want; at least you will be a free man.”

This article was originally published at Cairoscene. Amjad Abdelhady and Abed Al-Galaly contributed to this feature.

![IMG_20151011_183727[1]](https://valentinaprimo.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/img_20151011_1837271.jpg?w=1000)

Leave a Reply