The sun is falling on this rainy afternoon as we approach the Maasai village in Western Kenya. Perhaps because of the hills framing the mud houses on the opposite side, it feels like we are at the edge of the country.

We go past a pack of goats as they are herded by a tiny shepherd covered by a red tartan cape; the kid is about 9-years old. Around him, the goats’ bleat and their bells clinging seem to announce the prelude of a hard working day. Inside the mud houses, Maasai mothers prepare the stew.

We meet the chief, an old man covered in a bright violet cape whose serious, skeptical eyes carefully observe us. He doesn’t speak English. As Lepere begins to show us around, we enter a mud-house being built, where a stack of branches line up as they set out to become the bridal bed.

“Usually, the mother builds the house using mud, sticks, grass, cow dung and cow’s urine,” he explains. Women are not only responsible for making the houses; they also supply water, collect firewood, and milk the cattle. As we exit the house, a room awaits for the family’s cow. Every house reserves a room for cattle, which is not only protected as a commodity to be traded, but more importantly, the measure of a man’s wealth.

Traditionally a tribe of herders, the Maasai do not hunt. They graze cattle and used to cultivate the land, but the loss of territory brought along by the development of touristic national reserves led the tribe to reduce their plot sizes and farm. “Our people traditionally frown upon this. Maasai believe that utilising the land for crop farming is a crime against nature,” says the Maasai Association.

The subdivision of Maasai land to create national parks and reserves has restrained the tribe from accessing water, pasture, and salt lick, and reduced size for cattle herding has pushed them to poverty. Even though the concept of private territory was foreign to them, a programme to commercialise livestock and land was imposed by the British in 1960, subdividing the territory into groups and individual ranches.

We are led by Lepere into one of the mud houses, where a Maasai family awaits our visit. The interior is surprisingly small, organised around a bonfire where the stew boils. We sit in a circle on wooden benches against a wall which vibrates as a cow mooes in the opposite room. The light is dim, and we can barely see Lepere’s face, but we can hear his soft voice as he calmly shows us the utensils they use. The house, although tiny, is home to a family of seven people who live there for nine years. After this period, as termites begin to erode the constructions, all the tribe migrates to another village, where they begin building their new houses.

We look at the woman cooking the stew, and notice her head is shaved as well, just as the men. Her ears are pierced into big, long holes, where colourful earrings hang. Some men also have their ears pierced, indicating that they are the eldest son.

One figure, however, is particularly iconic: the Maasai warrior. At the age of 15, every Maasai man goes to the “bush” where he spends five years learning to survive in the Savannah. In order to become a warrior, they have to kill a lion. Only then, and with the proof of the animal’s tooth, can they come back to the tribe. In the past, warriors were trained to fight against other tribes for cattle and land. Nowadays, they defend their flock from the Savannah, as hyenas, cheetahs and lions often surround their villages.

Shaving their hair is for them part of a ceremony that marks the transition of a warrior and allows him to marry, and it is performed by the warrior’s mother. During the ceremony, called Eunoto, an animal horn is set on fire and warriors take a piece out before it is completely burned. “No one wants to take the piece out, because whoever takes the horn out of the fire will suffer misfortune throughout his entire life,” Lepere explains to us. The next day, Lepere would invite the men in our group to try cow blood, which they drink on special occasions.

Like Eunoto, there are plenty of ceremonies marking the different stages of life for the Maasai, although some of are eroding due to external influences and the incorporation of Western standards of life. These ceremonies are not only a rite of passage, but also an expression or identity and self-determination.

Tourism and the reality behind the show

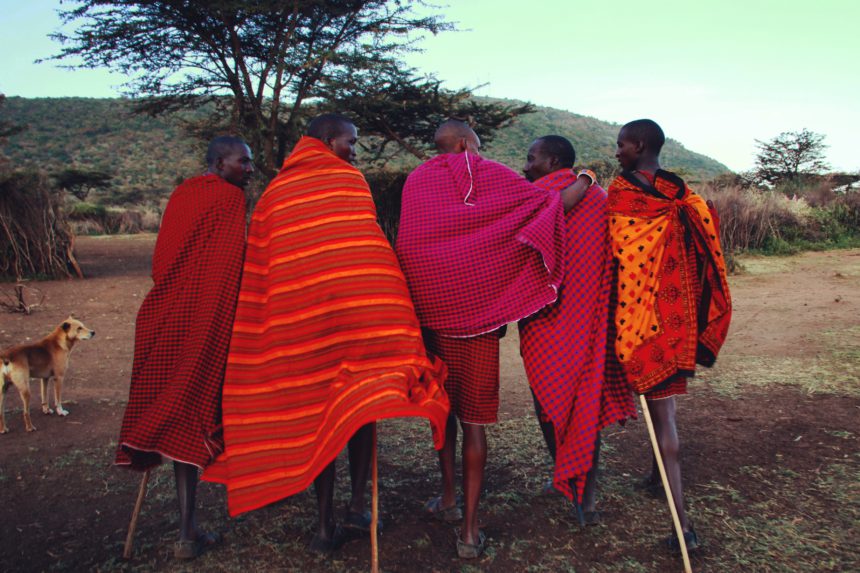

As we come out of the house, a group of Maasai men come to greet us. They stand in a line, begin singing and set up a ceremony, where each man performs the “jumping dance,” the Adumu. A competition between the dancers, the Adumu is a test to prove who can jump higher as a demonstration of manhood and bravery, says Lepere.

We feel the spectators of a show specially set up for tourists. We know that this is part of a routine sketch put up to give visitors a display of the exotic life they came in search for. And we can’t help but notice their watches, the occasional t-shirts, and the cell phones some of them have.

Tourism often turns tribal communities into a fetish of exoticism and expect to find them in a virginal state, uncontaminated; just as the spectacle they expect when visiting a zoo. However, away from the touristic fantasy of uncompromising cultures who do not give way to modern life, the Maasai have seemingly turned tourism into a form to secure the persistence of a culture they cherish. Some of them speak English, some of them ride motorcycles, and most children go to school, even though the uniform and the lessons can sometimes seem foreign to them.

“We are proud of our culture and we try to live the way our ancestors did,” Lepere tells us. Like his brother, he is one of six Maasai men employed by the touristic camp situated near the Maasai Mara reserve entrance. The game reserve, like the nearby Serengeti (in Tanzania), Ngorongoro, and Amboseli, is considered a protected area set aside for conservation, wildlife viewing, and tourism; therefore, the Maasai people are prohibited from accessing water sources and pasture land.

“It takes one day to destroy a house; to build a new house will take months and perhaps years. If we abandon our way of life to construct a new one, it will take thousands of years,” reads a Maasai belief highlighted by the Maasai Association.

Leave a Reply