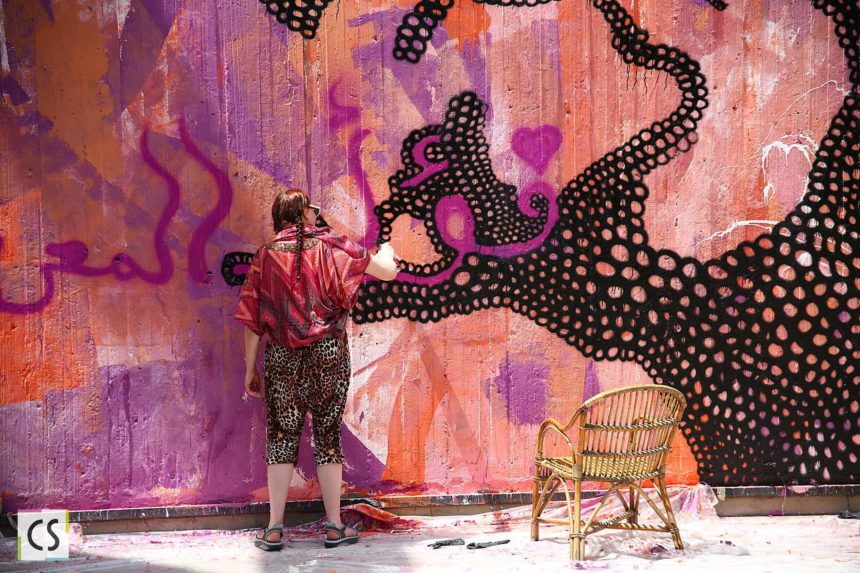

Valentina Primo heads out to the GrEEK Campus where Women on Walls – an initiative promoting, producing and protecting street art created by the fairer sex – has taken over the streets with powerful murals, only to find objections from other artists.

Apr 09,2015

As the Women on Walls initiative deployed a colourful array of murals and graffiti art in and around the GrEEK Campus in a statement for women’s rights, controversy broke out. Several murals appeared paint-splashed by fellow artists, in a battle of paint that claims to safeguard the memory of the revolution’s martyrs depicted on the ironic Mohamed Mahmoud Street.

“What we are witnessing here is the question of who is in control of the streets, the walls, the money – and who is in control of women,” says Mia Grondahl, founder of WOW and author of the photography book Revolution Graffiti: Street Art of the New Egypt. “It is sad, because I was hoping that street artists who call themselves ‘revolutionary’ wouldn’t attack projects supporting women and women’s rights.”

The event, a five-day graffiti workshop organised as part of the D-CAF festival’s 4th edition, gathered street artists from Jordan, Tunisia, Bahrain, UAE, Syria, Egypt and Sweden to paint murals on two walls of the GrEEK Campus: on Youssef El-Guindy and Mohamed Mahmoud street, a symbolic road considered by some graffiti artists as a necropolis where the revolution’s martyrs are depicted.

“The idea is not only to support women’s rights but also to encourage female graffiti artists and provide them with safe walls to do their art in peace,” says Grondahl. “I actually came up with the initiative after I went through my archive of graffiti photographs and realised that out of 17,000 pictures, only 250 were made by women,” she points out.

With the theme “Unchained”, the initiative is the third project created by Women on Walls, supported this year by the Swedish Institute and Centre for Culture and Development (CKU). Launched in Egypt in 2013, WOW is now growing network of over 60 artists that counts with an active branch in Jordan and regular events across the Middle East.

As the streets bustled with women painting on lifts at a height of 12 metres, critics began to pour. “It’s creating all kinds of strange feelings. People are afraid that we will ruin the wall, or paint over martyrs. But we would never do that, we are painting above them,” Grondahl explains. “The important thing is that this is happening, this is part of the communication. They call this street a necropolis, so does it mean we should respect the dead by not touching these walls? No, my understanding is that the respect to the dead is to make sure that we can get a good life for the future. And what these women are doing is showing people that they have something to give, that they have not given up,” she tells us.

Dina Saadi is one of the 20 street artists who flew to Cairo to leave her message imprinted on a mural. “This is not about the wall, it is about some people’s ego, and we are actually painting over ruined walls, leaving everything else intact. But just because a group of ladies decide to do something on the wall, then suddenly everyone is not happy about it. Well, I guess that is exactly why we are here,” the Syrian-Russian artist says.

Her mural, a human heart with a lock that has been open, reads ‘unlock your passion.’ “Chains are not only about society telling women what is not good or appropriate; it’s also about society not really believing in women, that we can do exactly the same as men do.”

On the adjoining wall on Youssef El-Guindy Street, Egyptian painter Salma Fahmy works on her mural, which she had originally intended to be a nude woman. “These are the chains we are trying to break. Chains mean, for example, the fact that I cannot draw a nude on the wall, that we are not able to do things that men are allowed to do like saying profanities and expressing our feelings,” says Fahmy, who also studies applied arts at the German University in Cairo.

Further above, Jordanian designer Yara Hindawi drawsanother heart with two pens on the sides, in a strong call for education of women in the Middle East. “What the image is trying to tell Arab men is not to be scared of disgracing their honor, because Arab women are not struggling to be educated so that they can just go out and write love letters,” she ironises. Just below her painting, Egyptian digital artist Gee El Shaikh focuses on mythology. “The three major religions that we know today are very limited in terms of gender,” she says. “But back in the days, mythology, especially that of ancient Egyptians, included gods and goddesses, a duality that I feel is missing nowadays and is deeply affecting our society: You hear more of the HE and less of the SHE.”

“Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly, is better than not to think at all,” the message reads below Hypathia, a mural painted by Egyptian artist Khadija Mostafa. The piece was one of the artworks ruined during the night, when an unknown man threw red paint on the wall, but she artist painted Hypathia again, this time with red strings in her hair.

This is not the first time the project was subject to aggression, its founder says. “From the beginning of WOW in 2013, I’ve been called ‘whore’, ‘the old woman’, and ‘witch’. My face has been stenciled on a wall, showing a woman ‘full of shit and dollars.’ Most recently I’ve received threats telling me that ‘the war is on’ and ‘you don’t want to know what’s waiting for you out there in our world of street art,’ together with a recommendation to pay $ 10,000 if I want to be left in peace,” she writes on a Facebook post.

Was graffiti art not so revolutionary, after all? “It is not for me to judge what is revolutionary or not. I have been in Egypt for 15 years, I am not here to create conflict. What I find deeply sad is that street artists and artists in general are people who usually want to be free, to create and express freely. They all share that feeling. So for one artist to come and restrict freedom for others is something I don’t understand. You want all the freedom for yourself but don’t allow it to others? It doesn’t make sense,” she says.

Street art has played a major role in Egypt’s revolutionary movement. A form of resistance, a tool to break chains and embody the social conscience of a society in deep transformation. But what happens when the struggle is over? “I think graffiti is always taking the temperature of the situation, it is always a reflection of what is going on. We have left a period that has been very chaotic, where there was lot of hope, fear and desperation, and now there is a sense of ’What was this all for?’ What the young women are doing is showing that life has different sequences, and they are making the best of the situation; they are not just sitting on a chair waiting and dreaming of the wonderful glories of the days of the revolution. And what just happened showed that the next revolution has to be about women.”

This article was originally published on Cairoscene.

Leave a Reply